Last week I joined the ALT Winter Summit on Ethics and an Artificial Intelligence. Earlier in the year I was following developments at the interface between ethics, AI and the commons, which resulted in this blog post: Generative AI: Ethics all the way down. Since then, I’ve been tied up with other things, so I appreciated the opportunity to turn my attention back to these thorny issues. Chaired by Natalie Lafferty, University of Dundee, and Sharon Flynn, Technological Higher Education Association, both of whom have been instrumental in developing ALT’s influential Framework for Ethical Learning Technology, the online summit presented a wide range of perspectives on ethics and AI, both practical and philosophical, from scholars, learning technologists and students.

Whose Ethics? Whose AI? A relational approach to the challenge of ethical AI – Helen Beetham

Helen Beetham opened the summit with an inspiring and thought-provoking keynote that presented the case for relational ethics. Positionality is important in relational ethics; ethics must come from a position, from somewhere. We need to understand how our ethics are interwoven with relationships and technologies. The ethics of AI companies come from nowhere. Questions of positionality and power engender the question “whose artificial intelligence”? There is no definition of AI that does not define what intelligence is. Every definition is an abstraction made from an engineering perspective, while neglecting other aspects of human intelligence. Some kinds of intelligence are rendered as important, as mattering, others are not. AI has always been about global power and categorising people in certain ways. What are the implications of AI for those that fall into the wrong categories?

Helen pointed out that DARPA have funded AI intensively since the 1960’s, reminding me of many learning technology standards that have their roots in defence and aeronautical industries.

A huge amount of human refinement is required to produce training data models; this is the black box of human labour, mostly involving labourers in the global south. Many students are also working inside the data engine in the data labelling industry. We don’t want to think about these people because it affects the magic of AI.

At the same time, tools are being offered to students to enable them to bypass AI detection, to ‘humanise” the output of AI tools. The “sell” is productivity, that this will save students’ time, but who benefits from this productivity?

Helen noted that the terms “generative”, “intelligence”, and “artificial” are all very problematic and said she preferred the term “synthetic media”. She argued that it’s unhelpful to talk about the skills humans need to work alongside AI, as these tools have no agency, they are not co-workers. These approaches create new divisions of labour among people, and new divisions about whose intelligence matters. We need a better critique of AI literacy and to think about how we can ask questions alongside our students.

Helen called for universities to share their research and experience of AI openly, rather than building their own walled gardens, as this is just another source of inequity. As educators we hold a key ethical space. We have the ingenuity to build better relationships with this new technology, to create ecosystems of agency and care, and empower and support each other as colleagues.

Helen ended by calling for spaces of principled refusal within education. In the learning of any discipline there may need to be spaces of principled refusal, this is a privilege that education institutions can offer.

Developing resilience in an ever-changing AI landscape ~ Mary Jacob, Aberystwyth University

Mary explored the idea of resilience and why we need it. In the age of AI we need to be flexible and adaptable, we need an agile response to emerging situations, critical thinking, emotional regulation, and we need to support and care for ourselves and others. AI is already embedded everywhere, we have little control over it, so it’s crucial we keep the human element to the forefront. Mary urged us to notice our emotions and think critically, bring kindness and compassion into play, and be our real, authentic selves. We must acknowledge we are all different, but can find common ground for kindness and compassion. We need tolerance for uncertainty and imperfection and a place of resilience and strength.

Mary introduced Aberystwyth’s AI Guidance for staff and students and also provided a useful summary of what constitutes AI literacy at this point in time.

Achieving Inclusive education using AI – Olatunde Duruwoju, Liverpool Business School

Tunde asked us how we address gaps in inequity and inclusion? Time and workload are often cited as barriers that prevent these issues from being addresses, however AI can help reduce these burdens by improving workflows and capacity, which in turn should help enable us to achieve inclusion.

When developing AI strategy, it’s important to understand and respond to your context. That means gathering intersectional demographic data that goes beyond protected characteristics. The key is to identify and address individual students issues, rather than just treating everyone the same. Try to understand the experience of students with different characteristics. Know where your students are coming from and understand their challenges and risks, this is fundamental to addressing inclusion.

AI can be used in the curriculum to achieve inclusion. E.g. Using AI can be helpful for international students who may not be familiar with specific forms of assessment. Exams trigger anxiety, so how do we use AI to move away from exams?

AI Integration & Ethical Reflection in Teaching – Tarsem Singh Cooner

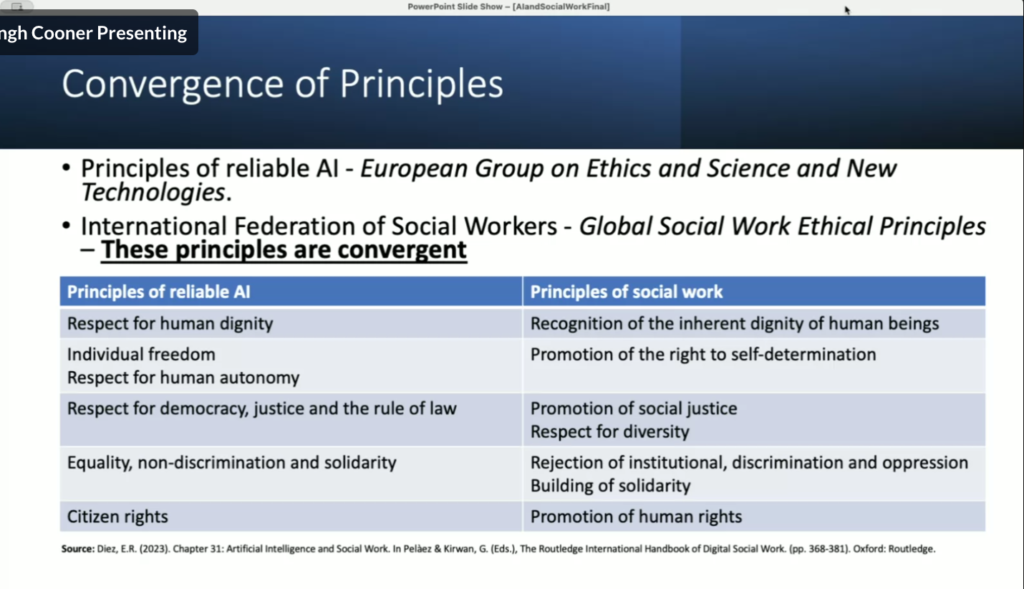

Tarsem presented a fascinating case study on developing a classroom exercise for social work students on using AI in practice. The exercise drew on the Ethics Guidelines on Reliable AI from the European Group on Ethics, Science and New Technologies and mapped this against the Global Social Work Ethical Principles.

The assignment was prompted by the fact that practitioners are using AI to uncritically write social work assessments and reports. Should algorithms be used to predict risk and harm, given they encode race and class bias? The data going into the machine is not benign and students need to be aware of this.

GenAI and the student experience – Sue Beckingham, Louise Drum, Peter Hartley & students

Louise highlighted the lack to student participation in discussions around AI. Napier University set up an anonymous padlet to allow students to tell them what they thought. Most students are enthusiastic about AI. They use it as a dialogue partner to get rapid feedback. It’s also helpful for disabled and neurodivergent students, and those who speak English as a second language, who use AI as an assistive technology. However students also said that using AI is unfair and feels like cheating. Some added that they like the process of writing and don’t want to loose that, which prompted Louise to ask if we’re outsourcing the process of critical thinking? Louise encouraged us to share our practice through networks, adding that collaboration and cooperation is key and can lead to all kinds of serendipity.

The students provided a range of different perspectives:

Some reported conflicting feelings and messages from staff about whether and how AI can be used, or whether it’s cheating. Students said they felt they are not being taught how to use AI effectively.

GCSEs and the school system just doesn’t work for many students, not just neurotypical ones, it’s all about memorising things. We need more skills based learning rather than outcome based learning.

Use of AI tools echoes previous concerns about the use of the internet in education. There was a time when there was considerable debate about whether the internet should be used for teaching & learning.

AI can be used to support new learning. It provides on hand personal assistance that’s there 24/7. Students create fictional classmates and partners who they can debate with. A lot of it is garbage but some of it is useful. Even when it doesn’t make sense, it makes you think about other things that do make sense.

A few thoughts…

As is often the case with any new technology, many of the problematic issues that AI has thrown up relate less to the technology itself, and more to the nature of our educational institutions and systems. This is particularly true in the cases of issues relating to equity, diversity and inclusion; whose knowledge and experiences are valued, and whose are marginalised?

It’s notable that several speakers mentioned the use of AI in recruitment. Sue Beckingham noted that AI can be helpful for interview practice, though Helen highlighted research that suggested applicants who used chatGPT’s paid functionality perform much better in recruitment than those who don’t. This suggests that we need to be thinking about authentic recruitment practices in much the same way we think about authentic assessment. Can we create recruitment process that mitigate or bypass the impact of these systems?

I particularly liked Helen’s characterisation of AI as synthetic media, which helps to defuse some of the hype and sensationalism around these technologies.

The key to addressing many of the issues relating to the use of AI in education is to share our practice and experience openly and to engage our colleagues and students in conversations that are underpinned by contextual ethical frameworks such as ALT’s Framework for Ethical Learning Technology. Peter Hartley noted that universities that have already invested in student engagement and co-creation are at an advantage when it comes to engaging with AI tools.

I’m strongly in favour of Helen’s call for spaces of principled refusal, however at the same time we need to be aware that the genie is out of the bottle. These tools are out in the world now, they are in our education institutions, and they are being used by students in increasingly diverse and creative ways, often to mitigate the impact of systemic inequities. While it’s important to acknowledge the exploitative nature and very real harms perpetrated by the AI industry, the issues and potential raised by these tools also give us an opportunity to question and address systemic inequities within the academy. AI tools provide a valuable starting point to open conversations about difficult ethical questions about knowledge, understanding and what it means to learn and be human.

This blog post was originally posted on the

This blog post was originally posted on the

I’ve already written a post about the joy of reconnecting with colleagues at the ALT Conference last month, but the conference also marked a significant end point for me. During the AGM, I formally stepped down from the Board of ALT, after my second term as a Trustee came to an end after six inspiring years. Earlier this summer my second term as a Wikimedia UK Trustee also came to close, so in some ways it feels a bit like an end of an era for me. Both organisations have been a significant part of my professional life for the last six years and it’s been an honour and a privilege to serve on these boards. I learned a huge amount from my fellow trustees over the years, and benefited enormously from working with a diverse group of people from a wide range of backgrounds, who I might not have had the opportunity to work with otherwise. I also really appreciated having the opportunity to engage with the wider learning technology and open knowledge communities at a senior level and to contributing to strategic initiatives. And perhaps most importantly, serving as a Trustee gave me an opportunity to give something back to ALT and Wikimedia UK, in return for their ongoing commitment to openness, equity, community engagement and knowledge activism.

I’ve already written a post about the joy of reconnecting with colleagues at the ALT Conference last month, but the conference also marked a significant end point for me. During the AGM, I formally stepped down from the Board of ALT, after my second term as a Trustee came to an end after six inspiring years. Earlier this summer my second term as a Wikimedia UK Trustee also came to close, so in some ways it feels a bit like an end of an era for me. Both organisations have been a significant part of my professional life for the last six years and it’s been an honour and a privilege to serve on these boards. I learned a huge amount from my fellow trustees over the years, and benefited enormously from working with a diverse group of people from a wide range of backgrounds, who I might not have had the opportunity to work with otherwise. I also really appreciated having the opportunity to engage with the wider learning technology and open knowledge communities at a senior level and to contributing to strategic initiatives. And perhaps most importantly, serving as a Trustee gave me an opportunity to give something back to ALT and Wikimedia UK, in return for their ongoing commitment to openness, equity, community engagement and knowledge activism.  Charlie talked about the GeoScience Outreach course where students co-create teaching and learning materials that are then adapted by Open Content Creation interns and shared on

Charlie talked about the GeoScience Outreach course where students co-create teaching and learning materials that are then adapted by Open Content Creation interns and shared on