The Stack Effect

Understanding the movement of air through a house can increase the comfort, energy efficiency, and healthfulness of your home.

Synopsis: Three forces move air through a house: HVAC equipment, wind, and the stack effect. Associate editor Rob Yagid explores how the stack effect works in both winter and summer. In the winter, cracks and openings throughout the building shell allow the pressure difference between indoor and outdoor spaces to drive air out of the top floor and to suck air in through the first floor. In the summer, when indoor air is cooled, the reverse occurs; however, because the temperature difference between inside and outside typically isn’t as great as it is in winter, the stack effect isn’t as great either. Whatever the season, the best way to remedy the stack effect in most houses is by air-sealing the house to minimize gaps between indoor and outdoor spaces.

It’s August, the dog days of summer, when your air conditioner hums endlessly and your electric bill skyrockets. Due to the stack effect, keeping the heat at bay can feel like a losing battle. The stack effect is a cyclical flow of air driven by differences between indoor and outdoor air densities and temperatures.

There are three forces that move air through a house: HVAC equipment, wind, and the stack effect. Of these, the stack effect is the least understood and at times the most powerful. By understanding this effect, you can increase the comfort, energy efficiency, and healthfulness of your home. Here’s how it works.

The heating season

The stack effect is strongest

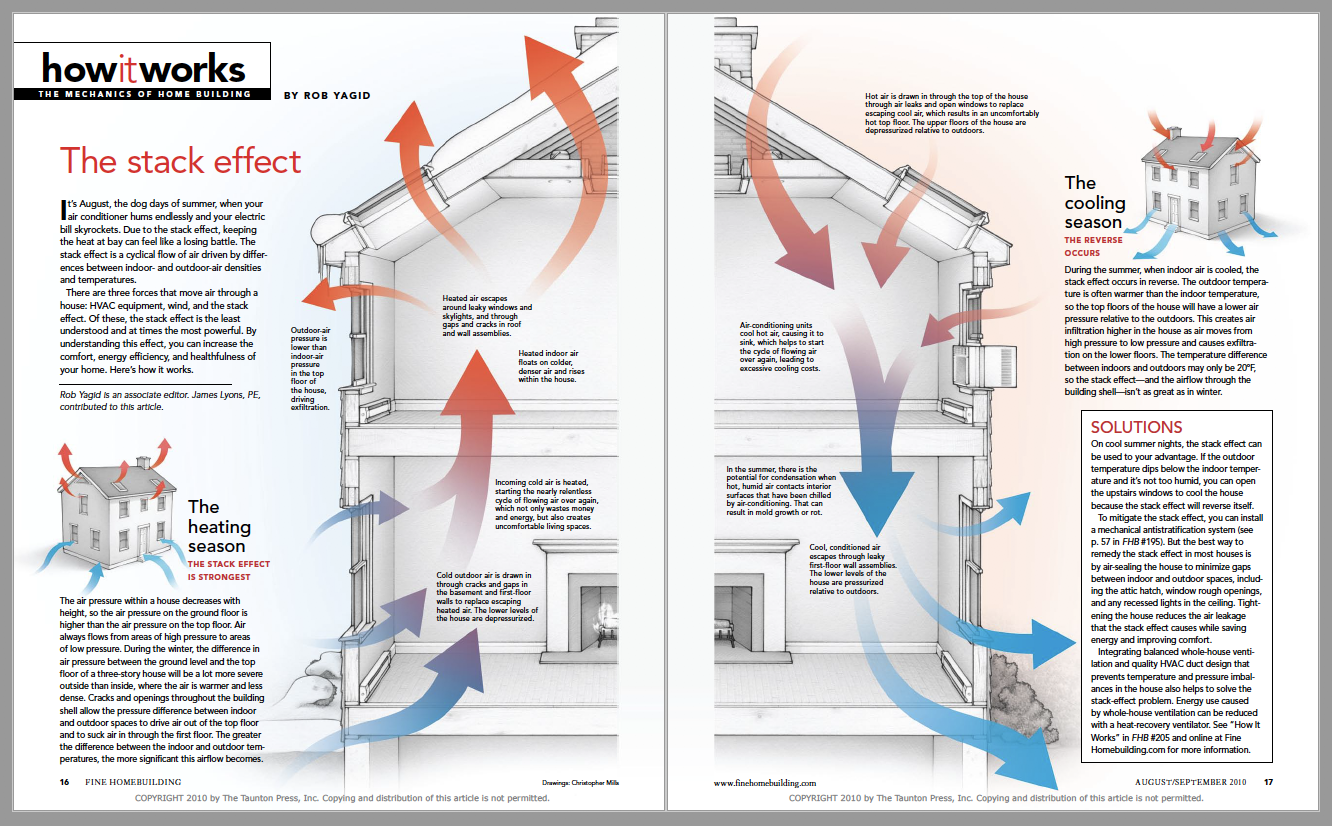

The air pressure within a house decreases with height, so the air pressure on the ground floor is higher than the air pressure on the top floor. Air always flows from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. During the winter, the difference in air pressure between the ground level and the top floor of a three-story house will be a lot more severe outside than inside, where the air is warmer and less dense. Cracks and openings throughout the building shell allow the pressure difference between indoor and outdoor spaces to drive air out of the top floor and to suck air in through the first floor. The greater the difference between the indoor and outdoor temperatures, the more significant this airflow becomes.

Cold outdoor air is drawn in through cracks and gaps in the basement and first-floor walls to replace escaping heated air. The lower levels of the house are depressurized.

Incoming cold air is heated, starting the nearly relentless cycle of flowing air over again, which not only wastes money and energy, but also creates uncomfortable living spaces.

Heated indoor air floats on colder, denser air and rises within the house.

Heated air escapes around leaky windows and skylights, and through gaps and cracks in roof and wall assemblies.

Outdoor-air pressure is lower than indoor-air pressure in the top floor of the house, driving exfiltration.

The cooling season

The reverse occurs

During the summer, when indoor air is cooled, the stack effect occurs in reverse. The outdoor temperature is often warmer than the indoor temperature, so the top floors of the house will have a lower air pressure relative to the outdoors. This creates air infiltration higher in the house as air moves from high pressure to low pressure and causes exfiltration on the lower floors. The temperature difference between indoors and outdoors may only be 20°F, so the stack effect and the airflow through the building shell isn’t as great as in winter.

Hot air is drawn in through the top of the house through air leaks and open windows to replace escaping cool air, which results in an uncomfortably hot top floor. The upper floors of the house are depressurized relative to outdoors.

Air-conditioning units cool hot air, causing it to sink, which helps to start the cycle of flowing air over again, leading to excessive cooling costs.

From Fine Homebuilding #213

From Fine Homebuilding #213

For more diagrams and details on how the stack effect works, click the View PDF button below.