Naked Joe

One hundred years ago, Joe Knowles stripped down to his jockstrap, said goodbye to civilization, and marched off into the woods to prove his survival skills. He was the reality star of his day. For eight weeks, rapt readers followed his adventures in the Boston Post, for whom he was filing stories on birch bark. When he finally staggered out of the wild, looking like a holdover from the Stone Age, he returned home to a heroâs welcome. Thatâs when things got interesting.

A stripped-down Joe Knowles on August 4, 1913, saying goodbye to well-wishers before heading off on his Maine wilderness adventure.

At first, as the train rolled into North Station on that crisp autumn morning a century ago, it looked like the police might lose their rein on the mob. There were an estimated 200,000 people on hand to greet the worldâs most unkempt celebrity, Joe Knowles, who was arriving from Portland on October 9, 1913. Men stood atop railroad cars, waiting. Female admirers lingered by the tracks, hoping for a private audience with Knowles, who, according to the Boston Post, had just completed âa most extraordinary experiment never before attempted by civilized man.â The stairs to the subway were so crowded that they resembled a âgrandstand at a football game,â the Post would report, and the crowds spilled out onto Causeway Street and around the corner onto Canal.

The throngs first spied Knowles sitting beside the window of the trainâs drawing room. A middle-aged man with an unruly gray beard and a long tangle of gray hair, Knowles was no Adonis. Indeed, he was a bit portly, at 5-foot-9 and 180 pounds. His muscle tone was about what youâd expect of a 44-year-old professional illustrator with a predilection for hanging about the taverns of Boston, where he regaled the boys with exuberant tales of his glory daysâthe 1890s, when he worked as a trapper and hunting guide in the woods of his native Maine. His gut hung. His arms bore some flab. Still, a few days hence, 400 coeds from Dr. Sargentâs Physical Training School for Women, in Cambridge, would stand in line waiting for the chance to touch his worn skin. Now, the crowds simply surged. Scores of policemen endeavored to hold them back as they rushed the train, and for a moment it seemed that chaos would erupt. This was a happy and civilized moment, however, and soon Knowlesâs fans stopped shoving and began bellowing cries of affection. âGreat work, Joe!…Youâre all right!…Youâre my bet!â

Then Joe Knowles emerged from the train, wearing a crude bearskin robe and grimy bearskin trousers. It wasnât a costume, exactlyâKnowles had established himself as the Nature Man. Two months earlier, he had stepped into the woods of Maine wearing nothing but a white cotton jockstrap, to live sans tools and without any human contact. His aim? To answer questions gnawing at a society that was modernizing at a dizzying rate, endowed suddenly with the motor car, the elevator, and the telephone. Could modern man, in all his softness, ever regain the hardihood of his primitive forebears? Could he still rub two sticks together to make fire? Could he spear fish in secluded lakes and kill game with his bare hands? Knowles had just returned from the woods, and his answer to each of these questions was a triumphant yes. In time, he would parlay his Nature Man fame into a five-month run on the vaudeville circuit, where he would earn a reported $1,200 a week billed as a âMaster of Woodcraft.â He would publish a memoir, Alone in the Wilderness, that would sell some 30,000 copies. He would even have his moment in Hollywood, playing the lead in a spine-tingling 1914 nature drama also called Alone in the Wilderness.

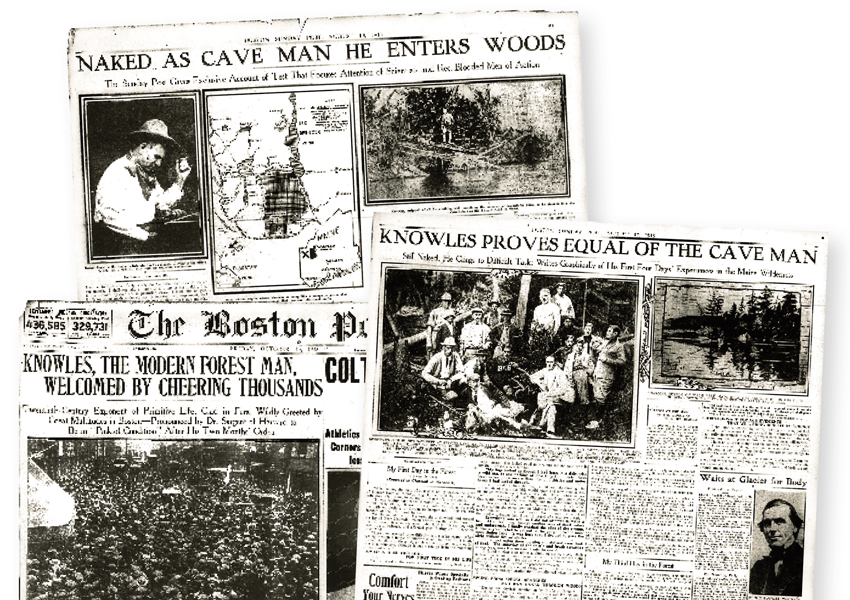

Knowles was the reality star of his day. On the Sunday after he set off, the Boston Sunday Post ran a whole special section on him, complete with a banner headline reading, âNaked as Cave Man He Enters Woods.â There was a ponderous studio portrait of him (he appeared in profile, with his head bowed as smoke plumed skyward from his cigarette), and there was also an affidavit, signed in cursive by 17 witnesses, affirming that Knowles had entered the woods at 10:40 a.m. on August 4 âalone, empty-handed and without clothing.â In an adjacent think piece, the Post quoted Dr. Dudley Sargent, the founder of the Physical Training School for Women, and also the âphysical directorâ at Harvard. âHis attempt to live like primeval man will have a scientific value,â Sargent declared. âWe will be interested to know how the lack of salt will affect Knowles.â

Knowles would soon become an asterisk of history. For now, though, after he emerged from that train, he followed the police out into the streets, then stepped into a waiting automobile for a parade. As the car began to move, he stood up, and pandemonium ensued. âThose nearest to the machine,â the Post reported, âthreatened to smash the running boards as they mounted the rims and mud guards.â

Eventually, Knowles reached Boston Common, where as many as 20,000 people were waiting for what, presumably, would be the most critical speech of Knowlesâs lifeâthe one public address that would distinguish him in the annals of American history.

Knowles climbed out of the car, made his way to the bandstand, and began to speak. âI will tell you one thing,â he told the crowd. âIt is a whole lot easier being in the woods than it is making a speech.â

He made a couple of vapid remarks. Then he got back in the car.

Joe Knowles lived in the golden age of publicity stunts. In 1901 a woman named Annie Taylor became the first person to descend Niagara Falls in a barrel. In 1911 Ralph âPappyâ Hankinson, a Ford dealer in Topeka, Kansas, invented the sport of auto polo to sell Model T cars. In 1924, to promote a movie, Alvin âShipwreckâ Kelly sat atop a high pole outside an L.A. theater for 13 hours and 13 minutes, launching a short-lived American craze for flagpole sitting. According to a condescending and scathing 1938 New Yorker story on Knowles, the Nature Man stunt was dreamed up by Knowlesâs drinking buddy, Michael McKeogh, a freelance writer. McKeogh read Robinson Crusoe and marveled over how the book, published almost two centuries earlier, was still selling briskly. Then, one night in 1913, in a smoky Boston saloon, as McKeogh listened to Knowles ramble on about his long-ago Maine adventures…light bulb! In his mindâs eye, he saw old Joe naked in the woods. âWeâll make a million,â he told Knowles. Then he drafted an outline of the drama (and of a prospective book) onto a notepad. âTuesday: kills bear,â he wrote, then asked, âBut are you sure you can do it, Joe?â

Hunched at the bar, Knowles described five or six ways that he could.

Knowles had recently worked at the Boston Post, a sleepy workingmanâs newspaper that was trying to stay alive in the nationâs most competitive media market. The city had 10 daily papers in 1913, and the Post was bleeding readers to the flashy upstart Boston American, which was financed by William Randolph Hearst, the father of yellow journalism. Knowles met with the Postâs Sunday editor, Charles E. L. Wingate, and proposed that the paper could boost readership by sending him to the Maine woods. He promised to produce drawings and status reports on birch bark, using charcoal, and to leave the documents in the crook of a designated tree. Hunting guides could then fetch them for McKeogh and other reporters, who would linger near Knowles, in a small cabin, and cast the whole tale as a fine, purple-tinged melodrama.

Wingate said yes to the scheme and agreed to pay Knowles a now-forgotten sum. His decision would prove brilliant. Between August and October 1913, the Post would later report, its circulation rose from 200,000 to more than 436,000.

Knowles in a bearskin robe on October 4, the day he reemerged from the wild.

The expedition began on a drizzly August morning, in a sort of no-manâs land outside tiny Eustis, Maine. The spot was some 30 miles removed from the nearest rail line, just north of Rangeley Lake, and east of the Quebec border. Knowles showed up at his starting point, the head of the Spencer Trail, wearing a brown suit and a necktie. A gaggle of reporters and hunting guides circled him.

Knowles stripped to his jockstrap. Someone handed him a smoke, cracking, âHereâs your last cigarette.â Knowles savored a few meditative drags. Then he tossed the butt on the ground, cried, âSee you later, boys!,â and set off over a small hill named Bear Mountain, moving toward Spencer Lake, 3 or 4 miles away. As soon as he lost sight of his public, he lofted the jockstrap into the brushâso that he could enjoy, as he would later put it in one of his birch-bark dispatches, âthe full freedom of the life I was to lead.â

On his own, Knowles kept hiking. It was raining. In bare feet, he slipped in the mud, but still he trudged on over the flank of Bear Mountain. Eventually, he spied a deer. âShe looked good to me,â he wrote, âand for the first time in my life I envied a deer her hide. I could not help thinking what a fine pair of chaps her hide would make and how good a strip of smoked venison would taste a little later. There before me was food and protection, food that millionaires would envy and clothing that would outwear the most costly suit the tailor could supply.â Knowles resisted the temptation to kill the deer, deciding to live within the game laws of Maine. He was hungry, wet, and cold, and also still a bit thrilled and agitated about being out there sans jockstrap. He could not sleep. What to do? He tossed off a few pull-ups. âOn a strong spruce limb I drew myself up and down, trying to see how many times I could touch my chin to the limb. When I got tired of this, I would run around under the trees for a while.â

If Knowles made himself sound like Tarzan, it was perhaps intentional. One of the most popular stories in Knowlesâs day was Tarzan of the Apes, an Edgar Rice Burroughs novella. Published in 1912 in the pulp magazine All-Story, it starred a wild boy who goes âswinging naked through primeval forests.â The story was such a hit that in 1914 it was bound into book form.

Pulp magazines (so named because they were published on cheap wood-pulp paper) represented a new literary form, born in 1896. They offered working-class Americans an escape into rousing tales of life in the wilderness. Bearing titles like Argosy, Cavalier, and the Thrill Book, they took cues from Jack London, whose bestselling novels, among them The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906), saw burly men testing their mettle in the wild. They were also influenced by Teddy Roosevelt, who insisted that modern man needed to avoid âover-sentimentalityâ and âover-softnessâ while living in cities. âUnless we keep the barbarian virtue,â Roosevelt argued, âgaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.â

Both Knowlesâs dispatches and the pulps represented a sharp departure from the pious nature writing that had prevailed in this country until about 1900, especially in New England. Thoreau had died in 1862, but at the turn of the century his heirs were still fixed on seeking wisdom, as opposed to adventure, in the outdoors. Bostonâs principal hiking group at the time was the Appalachian Mountain Club, and its members, says Christine Woodside, the current editor of the AMCâs journal, Appalachia, âwere often high-level academics, people from MIT or Harvard, who told themselves: âWe are deep thinkers about the wilderness and what it does for our character.â Theyâd come home and deliver academic papers or write journal articles.â

The editor of Appalachia from 1879 to 1919 was Charles Ernest Fay, a professor of modern languages at Tufts, and also an unabashed snob. In a 1905 Appalachia essay, âThe Mountain as an Influence in Modern Life,â Fay dismissed country people as incapable of enjoying the splendors of nature. âThe mountain dweller,â he wrote, âmay even look upon the towering masses that surround him as so much waste land, as occupying space that might otherwise come under tillage.â Fay advocated for a superior species: the mountaineer, who, though he sees the mountain only rarely, loves it âfor the grand anthem its forests sing to him, for the rich and varied gallery of Nature paintings that in sunshine and in storm, in the day-time and in the night season, it reveals to his eyes.â

Fayâs bald elitism had, of course, a long legacy in Boston. For most of the preceding century, the city had been lorded over by the Brahminsâthe Quincys, the Cabots, the Lowells, the Lodgesâwho sequestered themselves on Beacon Hill and shored up their wealth as they championed high-minded cultural institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. By 1913, though, the city had changed. With a population of 670,000, it was home to more than 200,000 recent immigrants, most of them Irish and Italian. In 1914 it would elect as its mayor James Michael Curley, a Catholic born in Roxburyâs Irish ghetto. Curley was so beloved that he was reelected as mayor three times, even though he was twice imprisoned for fraud. He was not a restrained individual. Once, in attacking an allegedly communist WASP political foe, he said, âThere is more Americanism in one half of Jim Curleyâs ass than in that pink body of Tom Eliot.â

As a newspaperman with artistic ambitions, Knowles was, socially speaking, a notch above the factory workers, bakers, and dockhands who made up Curleyâs core constituency, but he was still solidly ensconced in Bostonâs rising underclass. A grade-school dropout, Knowles grew up in Wilton, Maine, a tiny town about 40 miles northwest of Augusta. His father was a disabled Civil War veteran. His mother supported the familyâs four children by selling moccasins, as well as firewood and berries gathered in the forest. They were poor, and the subject of local ridicule. âThe schollars poked fun at my homespuns,â he wrote in an unpublished memoir, âtore the patches off my clothes, and stole my lunch…. And to make a good job of it, they broke up the bread and threw the crumbs to the birds.â

As Knowles tells it, his father bullied him, too, and when he was 13, after a paternal beating, he ran away, lying about his age so that he could work aboard cargo ships and travel the world. Knowles would eventually visit Cuba, South America, the Mediterranean, China, and Japan. By the time he was 17, heâd enlisted in the U.S. Navy and had returned to Wilton with a tattoo of a young woman twirling a snake. On another teenage return homeâa surprise visit made after two years at seaâhe arrived with a bottle of whiskey, a gift for his dad. His father did not say a word and did not touch the bottle. âHe just gave me a look,â Knowles wrote, âthat was all. That hurt more than all the lickings heâd ever given me.â

As dawn broke on his second day in the woods, Knowles fashioned a basket out of birch bark and began gathering berries. He speared two trout, but a mink stole them. He tried to light a fire, but the woods were still damp from the rain, so he simply built a shack out of dead sticks, fir boughs, and moss, and lay down, naked and hungry, in the forest duff.

The next day, Knowles sewed himself some witch-grass leggings and constructed a dam across Little Spencer Stream, to channel fish into a trap. On his fourth morning, he built a fire and ate baked trout for breakfast.

Then the reports stopped. For 11 days, no birch-bark dispatches appeared. The Post milked this silence for drama, reporting that Maine woodsmen believed him injured. Meanwhile, the paper squeezed all sorts of entertaining side dramas out of the Knowles saga. One story, titled âJoe Knowles Blew His Way To Fame,â recounted the Nature Manâs naval career. Another piece was titled âBoston Hunters Admire Knowlesâ âCave Manâ Feat.â

NATURE MAN: Before entering the woods, Knowles demonstrates âfire-making by friction.â

Readers did not hear from Knowles again until August 24, when, on page one, the Post ran a Knowles sketch of a wildcat, along with an alarming headline: âKnowles Catches Bear in Pit and Kills It with Club.â The bear was a yearling. It wasnât bear-hunting season in Maine yet, so the Post now had license to tantalize readers with the prospect of their heroâs arrest. One story read, âThe wardens are mustering the courage to tackle the Forest Man in his lair and drag him out.â

Did Knowles apprehend his legal danger? Did he flee to Quebec? For an October 5 story, an anonymous reporter made a âlong, hard trampâ of two days into Knowlesâs camp to answer these questions. He came away stumped and shivering, so he dwelled theatrically on the primitive trappings of Knowlesâs solitary existence: bits of bark chopped with blunt instruments, broken branches marking a crude trail, and a small lean-to. âHere was the scene of a great struggle,â the story read in a crescendo worthy of Jack London himself, ânot the marks of a physical battle, but the deeper, more impressive signs of a mental battle. For it was here a human being lived the strange life of self-imposed loneliness after he had fought and won his battle with nature. It was here he gathered crude comforts that would enable him to conform the civilized mind to primitive conditions.â

The Postâs dispatch noted that black bristles from the vanquished bear were âfound on many projecting points and on the upturned roots near the camp. On a rock was more hair, where evidently the forest man had been doing his tailoring.â But Knowlesâs bedclothes were absent, according to the story, and the bearskin was nowhere to be found.

Why? Because Knowles had taken it west. On the morning of October 5, the Postâs front page blared, âKNOWLES, CLAD IN SKINS, COMES OUT OF THE FOREST.â A subhead continued, âBoston Artist, Two Months a âPrimitive Man,â Steps into the Twentieth Century near Megantic, Province of QuĂ©bec.â Subsequent copy read, âTanned like an Indian, almost black from exposure to the sun…. Scratched and bruised from head to foot by briars and underbrush…. Upper garment sleeveless. Had no underwear.â

Picked up nationwide, the Postâs piece explained that Knowles had just traversed the most inhospitable portion of the Maine woods, after which, when he had emerged on the outskirts of Megantic, he had made his first human contactâa young girl he had found standing by the railroad track. âAnd the child of 14, wild-eyed, stared at him,â the story said, âand into her mind came the memory of a picture of a man of the Stone Age in a history book.â

âSomething within him rose,â the story continued, âand forced a cry from his throat, and kindly tears into his eyes. He smiled, and the girl saw the gold in his teeth flash. âHe is a real man,â she said to herself.â

Not everyone believed the story. In late October, after he had returned to civilization, an editorial in the Hartford Courant wondered whether âthe biggest fake of the century has been palmed off on a credulous public.â Meanwhile, a reporter from the rival Boston American had begun working on a long story about Knowles. The paper specialized in blockbuster exposĂ©s, and its investigative bloodhound, Bert Ford, had spent seven weeks combing the woods around Spencer Lake, aided in his research by a man he would call âone of the ablest trappers in Maine or Canada,â Henry E. Redmond.

On December 2, in a front-page article, Ford went public with the explosive allegation that Knowles was a liar. He zeroed in on Knowlesâs alleged bear killing, noting that the Nature Manâs bear pit was but 4 feet wide and 3 feet deep. In boldface, the story asserted, âIt would have been physically impossible to trap a bear of any age or size in it.â Knowlesâs club was likewise damning evidence. Found leaning against a tree, it was a rotting stub of moosewood that Ford easily chipped with his fingernails.

According to the Boston American, Knowles had a manager in the Maine woods, and also a guide who bought the bearskin from a trapper for 12 dollars. The bear had not been mauled, but rather shot. âI found four holes in the bear skin,â Ford averred after meeting Knowles and studying the very coat he was wearing. âExperts say these were bullet holes.â

Ford argued that Knowlesâs Maine adventure was in fact an âaboriginal layoff.â He wasnât gutting fish and weaving bark shoes, as the Postâs dispatches suggested. Rather, he was lounging about in a log cabin at the foot of Spencer Lake and also occasionally entertaining a lady friend at a nearby cabin.

Knowles responded to Fordâs story by filing a $50,000 libel lawsuit. In December he returned to his bear pit in Maine, this time with a small captive black bear. Then, watched by both reporters and Maine locals, he clubbed the poor animal to death and began picking at its skin with a sharp piece of shale. âIn less than ten minutes, he had the hide off one of the bearâs legs,â Helon Taylor, a 15-year-old witness, would marvel late in life. âWe were all impressed.â

But it was a sham. The bear was ready to hibernate, and so sluggish that Knowles had to prod it with a stick to make it put up a fight. Later, as Knowles and the spectators hiked out of the woods, Taylor spied a ânice, tight little log cabin,â so new that âthe peeled logs hadnât even started to change color.â Out behind the cabin, there was a pile of beer bottles and tin cans 4 feet high. Taylor suspected that Knowles had stayed there for the whole of his adventure, never once camping out.

A quarter-century later, in 1938, the New Yorker would corroborate Taylorâs hunchâand would also allow Knowlesâs ghostwriting âmanagerâ to reveal himself. He was none other than Michael McKeogh, the tavern habituĂ© whoâd dreamed up Knowlesâs wilderness stunt in the first place. McKeogh described Knowles as a melancholic louse. The Nature Man, he said, showed up at the cabin just hours after leaving his sendoff party at the foot of Spencer Trail.

According to the New Yorker story, Knowles entered wearing his jockstrap, sat down, and said nothing. He stayed for weeks. He was so morose and lethargic that when Maineâs game wardens came looking for him in late September, following the Postâs report about the vanquished bear, he shrugged off McKeoghâs entreaties that he run. McKeogh cried, âYouâll be put in prison, Joe, youâll be put in prison!â But Knowles moved only when he heard footsteps. And he only began his march toward Quebec after McKeogh hired an Indian guide to lead him through the forests that he had supposedly conquered.

BREAKING NEWS: The Boston Post made the most of Knowlesâs story in its pages. The paper got its information from dispatches that Knowles produced in the woods, by scribbling with charcoal on birch bark, and left for the paper in a pre-arranged dropoff spot.

Knowles was a nightmarish roommate for McKeogh during their time in the cabinâa hog who deprived McKeogh of lifeâs simplest pleasures. The worst of it came one day when McKeogh walked to the village of Eustis, 12 miles away, bought himself an apple pie, and carried it all the way back to the cabin. McKeogh placed it on the windowsill, to keep it cool overnight. The next morning, he heard the scuffling of feet behind him. He turned to see someone swiping the pie and trundling it off into the wilderness.

It was Joe Knowles. He ate the whole thing.

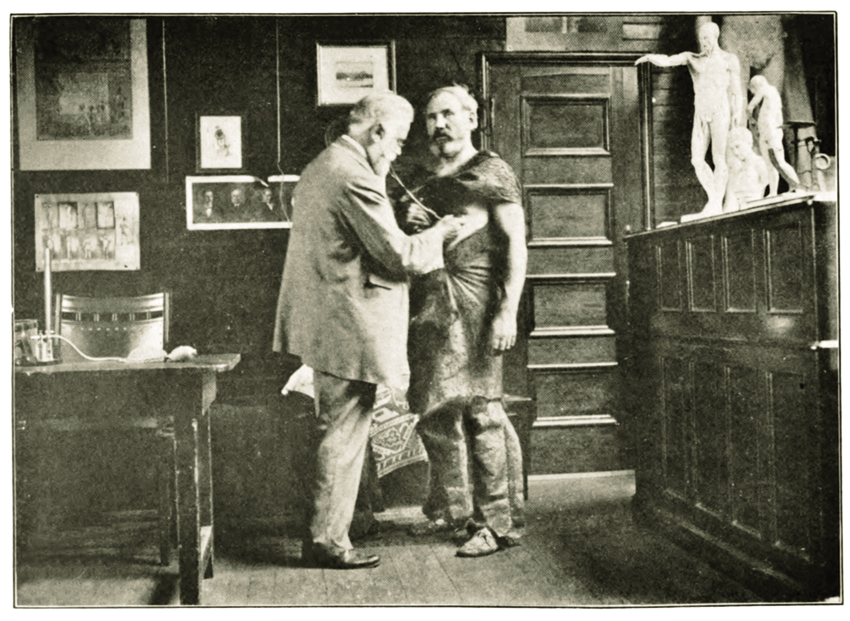

Nobody in Boston knew about this, of course. When Knowles finally returned to town, the city fathers embraced him as an emblem of virtue and hope. On October 11, an august assemblageââa host of New England physicians, sportsmen, and professional men,â as the Post described itâhonored Knowles with a black-tie banquet at the Copley Plaza Hotel. The gala was calibrated, it seems, to preempt naysayers and to sound hurrahs for a proud and growing city that had just opened the Franklin Park Zoo and was building its first real skyscraper, the 16-story Custom House Tower. The Honorable William A. Morse presided as emcee, and Dr. Samuel W. McComb, a psychologist, spoke, noting that Christopher Columbus had, much like Knowles, faced doubt after discovering the New World. âThe world is full of skeptics,â McComb said. âHowever, I think we may disregard them all.â Soon, Dudley Sargent, Harvardâs physical-education guru, rose and argued, improbably, that the 45-year-old Knowles was stronger than Harvardâs hardest football men. âWith his legs alone,â Sargent marveled, âhe lifted more than 1,000 pounds.â

A few days later, Knowles went on the vaudeville circuit. He worked on his book. And then, late in 1914, he made it to Hollywood, where in his one film he rode horseback through the ostensibly Canadian woods, over snowdrifts and across raging rivers, as he was chased (and falsely accused of murder) by Canadaâs North West Mounted Police. His mission was to save a beautiful starlet.

Knowles tried to get more movie gigs after that. A circa-1915 publicity shot shows him pitching himself as a heartthrob. Sitting on some porch steps in a fringed buckskin suit, he stares pouty-faced at the camera, his dreamy eyes filled with pained long-ing. Perhaps he was shilling for his own screenplay, The Poacher, an undated drama that was, as he himself described it, âa story of outdoor life in the game country of the Canadian Northwest.â The screenplay lists Joe Knowles in the starring role.

Knowlesâs movie career went nowhere. But in time, after settling on Washington stateâs Long Beach Peninsula in 1917, he would reinvent himself and find celebrity once again, as the illustrator of schlocky, canned images celebrating the American West. Knowlesâs drawings and paintings of Indians, shipwrecks, and animals were so popular that when his pet chipmunk, Mr. Peabody, died in 1939, the Oregonian ran an obituary. Knowles, the newspaper noted, habitually fed Mr. Peabody fresh green beans.

With humans, though, Knowles seems to have been less endearing. In his memoirs, he dismisses his working-class neighbors in Long Beach, saying, âThe natives do not interest me. They do not understand me, but I understand them, and they do not know it.â

Joe Knowles died in 1942. All of the 200,000 people who gathered at North Station to greet him are now probably dead, too, and his book is available in only a few libraries. A biography of Knowles, Naked in the Woods, by Jim Motavalli, appeared in 2008, but on the whole, this common manâs hero has in death met a common manâs fate: He has been forgotten. Or almost.

Today the worldâs most important repository of Joe Knowles material, arguably, is the Long Beach Peninsula Trading Post, a rambly antiques shop where, amid old postcards and license plates, thereâs a little shrine to Knowlesâa glass case displaying several of his etchings, as well as a few yellowing manila folders containing his memoirs.

Last fall, I traveled up to the Trading Post from my home in Oregon, a couple of hours away. I went as a pilgrim. In poring over the dusty troves of old news clippings, Iâd developed a warm appreciation for Knowles. He was a dyspeptic coot and a hard drinker, I canât deny that. He had no stage presence, and he was a liar. But by my lights he was still an American hero. He was like the Great Gatsby. He had chutzpah and grandiose ambitions, and in his own bumbling way he chased after his dreams.

I visited the Trading Post on a sunny Saturday morning, where, lounging on a couch, I leafed through the last musty remains of Joe Knowles. I read of a skirmish Knowles had late in life with an aging neighbor. In a long letter to his lawyer, he alleged that 65-year-old Hatty Harmon tried to poison him so as to take possession of his home, and called her an âold witchâ and an âold harlot.â In his unpublished memoirs, under the heading âPassing Thoughts,â he set down what could be construed as his closing argument. âLife is a queer game,â he wrote. âCheat a little here, bluff a little there, smile when it hurts, hide the truth, grab what you can while the grabbing is good, hold what you have. If you play the game according to these rules, you will win materially.â

Later, across the street, 94-year-old Adelle Beechey told me she remembered Knowles as a âfree thinker.â During the Depression, she said, he bought a car, even though he owed money at the local grocery store, and then took some friends out for a drive. âHis friends were nervous because, of course, he imbibed a bit,â she told me. âAnd when they came to a railroad crossing and found a train coming, Joe just kept driving. âDonât worry,â he said. âSheâs fully covered by insurance.ââ

In the end, I wanted to have my own moment with Joe Knowles, so I drove into the village of Ilwaco, parked my car, and walked down toward the beach. For the last two decades of his life, Knowles resided there, in what Motavalli calls a âcrooked cabin made of driftwood.â But that cabin vanished long ago, and even the topography of the place has shifted. The bluffs and fishing rocks that Joe Knowles walked by every day are now mostly erased. So I just strolled alongside the ocean as beachgoers flew kites and built sandcastles nearby. The sun was still high in the sky. It felt warm and good on my back, and I watched as its slanting light played tricks on the water.

Photo Album

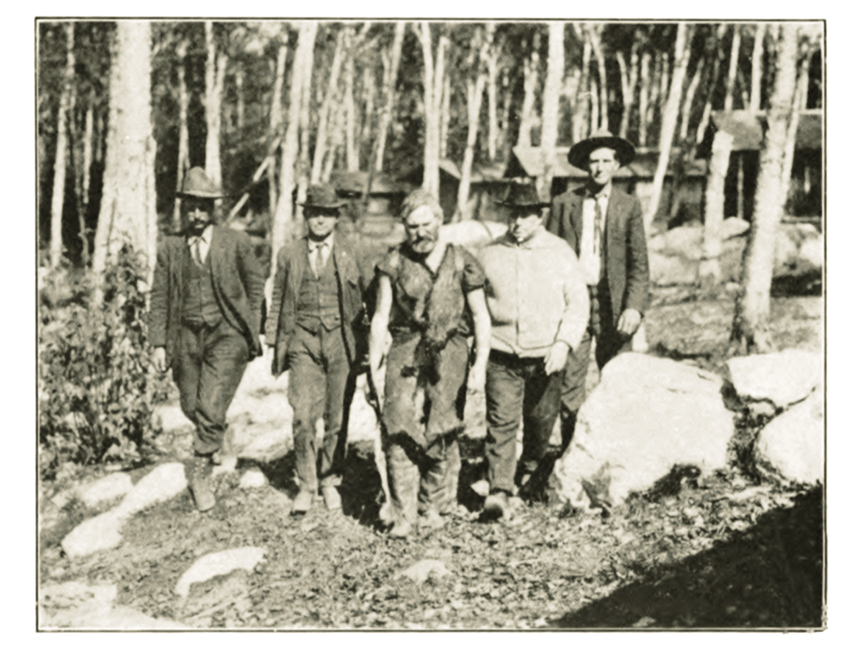

Game wardens escort Joe Knowles back to civilization on the day he emerged from the wilderness.

Harvardâs Dr. Dudley Sargent examines Knowles not long afterward.

A lean-to left behind in the woods by Knowles.

Crowds gather in Boston to cheer Knowles on during his triumphant return to civilization.

Knowles greets his mother at the end of his long ordeal.

A pair of shoes fashioned by Knowles out of cedar bark.

One of the birch-bark dispatches, written in charcoal, that Knowles left in the woods for the Boston Post to collect.

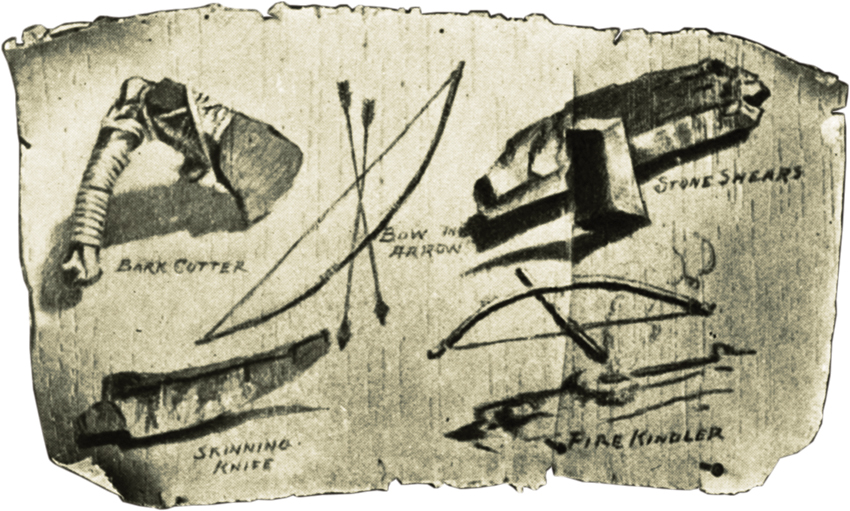

The Birch Drawings

Knowles deployed his talents as an illustrator to sketch scenes from the wilderness, drawing with the tips of burnt sticks on scraps of birch bark.

Source URL: http://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/article/2013/03/26/naked-joe-knowles-nature-man-woods/