Ileana Epsztajn, pour le blog Insights de l’OCDE

À 25 kilomètres de Paris, dans les Yvelines, la ville de Trappes comptabilise le plus grand nombre de départs pour la Syrie en Europe. Comment cette ville, lieu de naissance de nombreuses célébrités françaises comme Jamel Debbouze, Omar Sy, Nicolas Anelka ou encore Sofia Aram, en est-elle arrivée à ce triste record ?

GLYN KIRK / AFP

C’est l’une des questions que se sont posées Raphaëlle Bacqué, grand reporter au Monde, et sa collègue Ariane Chemin. Ensemble, elles ont passé une année à Trappes, pour tenter de comprendre l’évolution de cette communauté et d’en rendre compte dans un livre*, dont Raphaëlle Bacqué est venue parler au Forum de l’OCDE.

Développés dans les années 1960, les nouveaux quartiers de Trappes sont pensés comme une utopie urbaine par sa mairie, communiste depuis 1944, avec des bâtiments bas et des espaces verts pour éviter les inconvénients de la banlieue. Mais, au fil des années, les familles françaises et d’origine italienne ou portugaise quittent la ville, et le taux de la population nouvellement immigrée progresse de 325 % entre 1968 et 1975. Au cours des années 1980, la délinquance croît à mesure que s’étiole la mixité sociale. Et pendant les deux décennies suivantes interviennent des événements qui finiront de retrancher et d’isoler la ville. Dans les années 1990, le grand lycée, qui accueillait à la fois les enfants de Trappes et ceux des riches communes alentours, est doublé d’un second lycée vers lequel s’exilent tous les élèves de la classe moyenne et aisée. Puis, au début des années 2000, un nouveau maire, socialiste, gagne la ville contre la promesse de construire une grande mosquée à Trappes. Là où le parti communiste avait longtemps organisé le social dans la ville, c’est la religion, un islamisme proche des Frères musulmans, qui va s’immiscer.

Et la communauté sociale, économique et géographique constituée par cette ville a ainsi dérivé vers un communautarisme religieux. Aujourd’hui, comme le raconte Raphaëlle Bacqué, les habitants de Trappes disent : « Nous sommes entre pauvres ». C’est une commune qui revendique maintenant son enfermement : rien n’en sort (l’auteure raconte que pendant une année entière, le sujet de son livre, resté secret, n’a pas fuité, protégé par la barrière étanche du périphérique) et rien n’y rentre. Et pour ceux qui en sont sortis, comme les stars de l’écran ou du sport qui ont bénéficié d’une époque plus propice à l’intégration et à la mixité, il est difficile de revenir : on leur en veut.

Comme le résume Raphaëlle Bacqué, Trappes « est comme un laboratoire des tentatives et des échecs des politiques publiques dans nos banlieues ». Ou, comme le constatait plus amèrement un habitant de la ville présent dans le public du Forum, « Si beaucoup des enfants des Trappes sont partis en Syrie, c’est que les politiques publiques ont complètement abandonné la ville. »

Liens et références

Raphaëlle B. et A. Chemin (2018), La Communauté, Éditions Albin Michel, Paris.

Voir la session du Forum de l’OCDE 2018 « Rencontre avec l’auteur : La Communauté (avec Raphaëlle Bacqué) »

Travaux de l’OCDE sur le développement régional, urbain et rural

Gabriella Elanbeck and Rory Clarke, OECD Observer

Enlarge

© Keith Meyers/The New York Times/REA

New York City has one of the highest average population densities in the world, and few other US cities share its concentrated hustle and bustle. In fact, most of them face an entirely different challenge: urban sprawl.

The average number of inhabitants per km2 of populated urban space is actually very low in the US, as our chart shows. So while New Yorkers must grapple with the difficulties that accompany larger numbers of people in limited urban space, such as congestion and high rents, people in low density cities face long commutes and costly public service provision.

The US is not alone. While average population density in the urban areas of OECD countries is high in Korea and Japan, it is low in countries such as Austria and Canada. But even in those countries and cities with high average densities, urban sprawl must be confronted.

People’s lives may suffer, as this scattered and decentralised city growth can lead to environmental damage, social exclusion, and pressures on transportation and public services, as well as high public and private costs. What can policymakers do?

Finding sustainable solutions to reduce sprawl demands rethinking urban space and weighing the private benefits of low density living–my house and garden–against social, environmental and infrastructure costs. Compact cities, which balance dense development patterns, strong public transport linkages, accessibility to local services and jobs, affordable houses and healthy open spaces, can provide an answer.

Links and references

OECD (2018), Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://oe.cd/urban-sprawl.

OECD (2018), Average population density in urban areas of 29 OECD countries, 2014, https://oe.cd/pop.

©OECD Insights July 2018

Michael Morantz, OECD Public Governance Directorate

In a small town just outside Montreal, Jake [not his real name] struggles with drug addiction. His dependence on numerous substances has brought him in and out of hospital and rehabilitation programmes many times. What is striking about Jake’s addiction is how he acquires the drugs: not from a neighbourhood drug dealer, but through the post and courier companies. “It’s remarkably easy business,” he says. “Just like buying common, everyday items on the surface–as opposed to dark–web. Only there are a few extra steps. After you provide your false personal and delivery information and whatever sum of money is agreed upon, your package arrives at the designated address disguised as something else in order to get through the postal service.”

That “something else” is any of the countless innocent things we buy on the internet and have delivered to the house. Like a pair of shoes. A car part. A smart phone. A handbag. A children’s toy. Thanks to e-commerce, we can purchase these things from nearly anywhere in the world. This has led to a flood of small, individual packages that transit through international shipping every day. The packages arrive at customs facilities by the truck- or plane-load, often with little or no advance information other than the label affixed to the top of the parcel. And even when the information on the labels is accurate, how can inspectors possibly inspect each box and effectively risk-assess the contents without advance information? Criminal networks throughout the world are exploiting this gap.

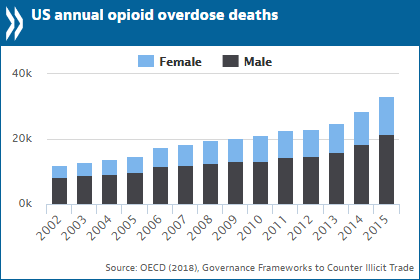

Small package trade is facilitating the global trade in counterfeits. The total value of fakes shipped globally was $US461 billion in 2013, or 2.5% of global trade, the OECD’s Task Force on Countering Illicit Trade estimates. Of this, over 60% of seizures by volume occurred in the mail stream in small packages. It is also one of the reasons why the current opioid epidemic has reached the proportions it has. The Center for Disease Control in the US reported a 30% increase in opioid overdoses nation-wide in 2016-2017. The high potency of fentanyl, the drug responsible for many of these deaths, means that an importer can smuggle tens of thousands of potentially fatal doses in a single small parcel.

Governments now realise the serious effects the small package trade can have. In an OECD report from 2018 on illicit trade, customs agencies reported that small, low-value shipments are a very real threat to national health, safety and security. Small parcels do not just contain illicit narcotics, but weapons, illegal wildlife products, or indeed nearly anything that will fit in a box.

A small-package delivery system which escapes controls has combined with the democratisation of trade through e-commerce to ignite a boom in illicit trade. Unlike illicit narcotics, customers need only go on the “surface web” to purchase counterfeits from e-stores. Popular social media sites make it even easier to access these marketplaces where you can buy anything from fake shoes and designer watches to deadly fakes like counterfeit medicines.

The trouble is that customs agencies are geared to monitor large commercial shipments rather than a continuous flow of small parcels. Can they adjust? Luckily, this change in the nature of trade is not unprecedented. In the 1970s, authorities had to adapt to “containerised trade”, for instance. The global challenge for customs officials then was to examine and risk-assess goods loaded on and off ships in large, locked steel containers. Customs administrations gradually developed a host of measures to deal with this, such as advance commercial information requirements integrated into risk-assessment software and other trade facilitation procedures. International co-operation among law enforcement bodies was also key to ensure the process went smoothly. Today, many customs administrations can target and risk-assess containers days before they arrive, and scan entire containers without opening them. However, now they must adapt to high-volume shipments of small consignments.

The speed and agility of criminal networks are such that authorities are almost always playing catch-up. And they are doing so in the dark. The same goes for the customers and victims of the shadow economy. Jake notes, “I have no idea where the drugs come from, I have no idea who makes them and I have no idea of their quality. But that’s the name of the game.”

It doesn’t have to be. Though the institutional capacities of individual law enforcements agencies are weak, governments can co-operate with each other, and with courier services, postal administrations, e-commerce vendors and intermediaries, using fora such as the OECD’s Task Force on Countering Illicit Trade. Without these international partnerships pushing for effective regulatory reforms, illicit e-commerce will continue to enrich these criminal networks. People like Jake should not have to pay the price.

Links and references

OECD (2018), Governance Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris,http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264291652-en.

OECD/EUIPO (2017), Mapping the Real Routes of Trade in Fake Goods, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278349-en.

OECD/EUIPO (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252653-en.

OECD (2016), Illicit Trade: Converging Criminal Networks, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264251847-en.

OECD Task Force on Countering Illicit Trade (TF-CIT), www.oecd.org/gov/risk/oecdtaskforceoncounteringillicittrade.htm

See “Opioid Overdoses Treated in Emergency Departments” at www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-overdoses/index.html

©OECD Insights May 2018

Balázs Gyimesi, OECD Observer

“Sorry, our website is temporarily unavailable.” While this message may cause you some inconvenience when surfing the web, it’s costly for companies. For over 50% of firms, the unavailability of their sites can cost as much as US$1,000 per minute. And technical shortcomings are not the only reason websites go down–targeted cyber attacks are too.

Cybercriminals bombard servers with traffic to overburden websites. These “denial-of-service” attacks (DoS) affect firms of all sizes in every region. In October 2016, a network of internet-connected devices attacked the servers of Dyn, a provider of domain name system services. It temporarily shut down several major websites in the US and Europe, including those run by television channel CNN, The Guardian newspaper, Netflix, a film entertainment company, and social media giant Twitter. While the cyber attack was neutralised in just over two hours, it caused business losses of an estimated US$110 million.

This was an especially damaging denial-of-service attack compared to the average, whose cost is estimated at over US$50,000 for small firms and nearly US$450,000 for larger businesses. And the number of these harmful attacks is on the rise, targeting mostly government, media and financial services. After a peak of 4919 DoS attacks in the second quarter of 2016, the number fell to around 3164 in the first quarter of 2017, but rose again in the second quarter of 2017 to 4051.

Insurance can help companies be more resilient to cyber risks but there are challenges that need to be overcome before the cyber insurance market can reach its full potential. Governments should also support initiatives aimed at sharing knowledge and expertise on risk management practices, as set out in the OECD Recommendation on Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity. When a DoS attack happens, every minute counts–we need responses to restore service now.

OECD (2018), The cyber insurance market: Responding to a risk with few boundaries, www.oecd.org/finance/insurance/The-cyber-insurance-market-responding-to-a-risk-with-few-boundaries.pdf

OECD (2018), Unleashing the Potential of the Cyber Insurance Market: Conference outcomes, www.oecd.org/daf/fin/insurance/Unleashing-Potential-Cyber-Insurance-Market-Summary.pdf

OECD (2017), Enhancing the Role of Insurance in Cyber Risk Management, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264282148-en

OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation on Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/digital-security-risk-management.pdf

OECD Unleashing the potential of the cyber insurance market, videos and conference summary: http://www.oecd.org/finance/2018-oecd-conference-cyber-insurance-market.htm

Digital Attack Map, www.digitalattackmap.com/about/

©OECD Insights May 2018

Peter Berlin, OECD Observer writer-at-large

Recently, a group of 15-year-old students from a girls’ secondary school in the Palestinian Authority audited the construction of a swimming pool in their town. Part of a competition organised by Integrity Action, a civil society organisation, the girls chose to do this because the local government had decided to build a male-only pool and they felt it was not meant for the whole community.

The girls visited the site and requested and examined all the papers related to the project, including the bills and the blueprints. They found that the lifeguard was unqualified and that the tiles were not of the quality specified in the contract. So they made a fuss.

The builder replaced the tiles. The town hired a real lifeguard and said it would think about adding screens for privacy and opening the pool for women on certain days.

“Working on this project was one of the most successful things we did in our lives. We were finally able to raise our voices and make them heard by decision-makers. We forced them to fix the problems!” said the students.

Fredrik Galtung, the founder and president of Integrity Action, told this story at “The Kids are Alright: Educating for Public Integrity”, a session at the OECD’s Global Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum at the end of March.

Other sessions ranged from meetings of auditors on infrastructure, norms and standards to topics like corruption in sports, business ethics, human slavery and the law of the sea.

“Planet Integrity is not a distant dream, it’s an urgent necessity,” OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría said in his opening remarks.

The cross-border reach of corruption and the problems it poses to national agencies was echoed repeatedly at the forum. “Slavery and human trafficking have no borders,” said Monique Villa, CEO of the Thomson Reuters Foundation and founder of TrustLaw and Trust Women.

In the session on sport, Ronan O’Laoire, Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Officer, talked about the “perfect circle” of betting, money laundering and match fixing, with criminals in one country using the globalised betting markets to profit from sports events in other continents.

The cross-border problem is exacerbated by the speed with which the corrupt hop to new honeypots and how fast they adapt to technological and social changes, such as the dark web, e-trade and cryptocurrencies.

“Corruption is a moving target,” Mr Gurría said. “Corruption is often a faceless and borderless crime. Illicit financial flows, cybercrimes and human trafficking are the ‘dark’ side of globalisation. Tackling this must be a global priority.”

John Penrose, a British MP who has been appointed his country’s “anti-corruption champion” was worried: “We are slower than the corrupters at the moment. They are way ahead of us.”

Marcos Bonturi, who heads the OECD’s Directorate for Public Governance, said that people are our best weapon against corruption. “We have been too focused on legal implementation but we’re no longer ignoring the human dimension–how individuals see themselves and relate to society and how education can create a culture of integrity.”

He added, “But we cannot do that overnight. It takes a generation or two. We need to start now.”

That high-school students investigated the accounts of a community swimming pool and found information that led to changes is the kind of grass-roots activism that will beat corruption. But it’s an active vigilance that has to be taught, and taught while people are still young. Mr Galtung summed it up neatly: “Corruption is a skill set. Integrity is a skill set.”

NOTE: The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Links

www.oecd.org/corruption/integrity-forum/

www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/integrity-education.htm

©OECD Insights May 2018

Anne-Lise Prigent, L’Observateur de l’OCDE

Chaque année, entre 1500 et 2000 milliards de dollars partent en fumée en pots-de-vin, soit 2% de l’économie mondiale. Il ne s’agit là que d’une partie infime de la corruption qui gangrène la planète. Cette corruption nourrit le terrorisme, le changement climatique ou encore la crise des réfugiés. Elle mine la confiance des citoyens dans les gouvernements et les marchés. La corruption peut également tuer, par exemple quand des bâtiments sont érigés au mépris des normes techniques afin de gagner des contrats et de remplir quelques poches. La corruption nuit sérieusement au développement.

C’est pourquoi le combat contre la corruption et les pots-de-vin fait partie intégrante des Objectifs de développement durable (objectif 16-5). Et il ne pourra être gagné sans la meilleure des armes : la coopération.

Pourtant, alors qu’une armée est déjà – par nature – stratégiquement déployée dans presque tous les pays du monde, on ne l’utilise pas – ou pas assez, comme je le souligne dans cet article.

Les contrôleurs fiscaux sont idéalement positionnés pour repérer les transactions suspectes. Ils pourraient aider à barrer la route de la corruption, comme ils ont barré celle d’Al Capone en son temps. Mais pour cela, il faudrait mettre en place une vraie coopération entre les autorités fiscales et celles qui luttent contre la corruption.

Car les chiffres laissent plutôt rêveurs. Parmi toutes les affaires de corruption internationale liées à des pots-de-vin, combien ont été détectées par les autorités fiscales entre 1999 et 2017 ? Un pour cent. Oui, un pour cent…

On a donc d’un côté des enquêteurs et procureurs fiscaux qui cherchent à traquer les cas de corruption. Et de l’autre, des contrôleurs fiscaux qui ont accès à une mine d’information. Ces deux équipes naturellement complémentaires ne jouent pas assez ensemble.

Pendant ce temps, les acteurs de l’économie criminelle coopèrent et prospèrent.

Pouvons-nous renverser la vapeur ? Oui, si nous le voulons. Le Forum mondial 2018 de l’OCDE sur l’intégrité et la lutte anti-corruption a montré comment.

L’Observateur de l’OCDE vous en dit plus ici : La fiscalité à l’assaut de la corruption : ce que peut la coopération.

©OECD Insights, avril 2018

Anne-Lise Prigent, OECD Observer

Every year, bribes eat up an estimated 1 500 to 2 000 billion dollars, the equivalent of 2% of the global economy. And this is just a tiny fraction of the corruption that infects our world, feeding terrorism, climate change and the refugee crisis. Corruption undermines the public’s trust in government and markets, and holds back development. Corruption can even cost lives, as the likes of building and engineering standards are secretly bypassed to win contracts and line a few pockets, sometimes with tragic consequences.

No wonder the fight against corruption and bribery is built into the Sustainable Development Goals in Target 16-5. But the fight will not be won without co-operation and, as I highlight in this article, this sorely underused weapon could become very powerful if properly deployed.

Take the world’s tax inspectors. We have a veritable army at our disposal which is already strategically deployed in the field, in virtually every country in the world. Surely our tax inspectors could be trained to spot suspicious transactions. They could help stop corruption in its tracks, as they stopped Al Capone. For this to happen, we need more co-operation between anti-corruption and tax authorities.

How many of the international corruption cases linked to bribery between 1999 and 2017 were brought to light by tax authorities? Barely 1%. Yes, 1%!

There are investigators and prosecutors tracking down corruption cases. And then we have tax inspectors with access to a mine of financial information. But the two teams rarely co-operate, rarely join the dots.

Meanwhile, the bad guys don’t work in silos and business is booming.

Can we change this? Yes, we can if we want to. The OECD’s 2018 Global Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum took a good hard look at the situation.

Read my article in the OECD Observer: Tackling corruption through taxation: The power of co-operation.

©OECD Insights April 2018